About the Oude Kerk

The Oude Kerk, in the middle of the historic city centre, is a place for contemporary art and Amsterdam’s oldest building.

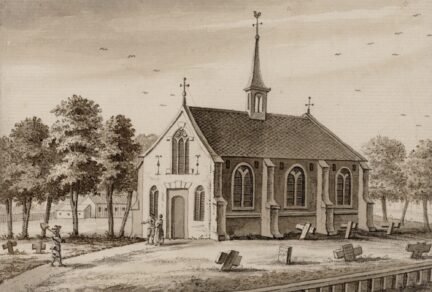

Over the centuries, the church grew from a small wooden chapel (circa 1250) to an extensive hall church (circa 1570). Today, the building is considered an important (inter)national monument. The Oude Kerk invites artists to create new works exclusively for this location. The programme connects past, present and future through the interplay of ancient heritage and contemporary art. The new works artists and musicians create here offer new perspectives on history, the world around us, and the future.

A short history

Wooden chapel on a levee

Where the River Amstel culminated in the River IJ, it would deposit clay sediment, creating mounds or levees. In the 13th century, the city’s first inhabitants built a church on one such spot, which also served as a cemetery. The church has since become one of Amsterdam’s most impressive monuments.

Sint Nicolaaskerk becomes Oude Kerk

The building became the Sint Nicolaaskerk (Saint Nicholas Church) on 17 September 1306, when the Bishop of Utrecht consecrated it to Saint Nicholas, the patron saint of sailors. However, by the 1400s, a new church was needed as the city expanded and its population grew. In 1409, the Nieuwe Kerk (New Church) was consecrated on Dam Square. The Sint Nicolaaskerk thus became locally known as the Oude Kerk (Old Church). The building has been expanded over the centuries, including in 1552 with the addition of the Lady Chapel, above which are the stained-glass windows.

Iconoclasm destroys interior

The Oude Kerk is one of Europe’s most important Reformation monuments. Its austere interior reflects its dramatic change from a Catholic to a Protestant place of worship. The church was devastated during the iconoclasm of the Beeldenstorm and later the Alteratie (Alteration) of Amsterdam, when the Catholic city council was desposed on 26 May 1578. Statues were smashed, altars removed, images painted over, and ceremonial silver was stolen or melted down. The text on the choir screen refers to the Alteratie and bears witness to this historic revolt. It translates as ‘The misuse, gradually brought into God’s church, was here again undone in the year seventy-eight.’ The church was now for preaching, and Catholic Mass became a thing of the past. Protestant worship still takes place at the Oude Kerk on Sunday mornings.

Connected to world history

The history of the Oude Kerk partially intersects with the colonial past of the Netherlands. The church could exist, flourish, and expand partly thanks to the proceeds of the major trading companies in the Golden Age. Among the approximately 60,000 people buried in the Oude Kerk, we have thus far found one enslaved man: Jacob Beeldsnyder. However, on stained glass windows, gravestones, and panels, the names and coats of arms of various families are immortalized, some of which were involved in slavery and exploitation. Thus, the Oude Kerk serves as a reminder of a painful part of history, prompting ongoing reflection for us. It receives attention, among other things, in our art commissions.

Final resting place of many renowned Amsterdammers

Since the thirteenth century until 1865, around 60,000 people have been buried under more than 2,000 tombstones in the Oude Kerk. Among them are mayors, wealthy merchants, seafarers, and artists. One of the most famous graves is that of Saskia Uylenburgh (1612-1642), Rembrandt's first wife and muse. You can find her grave near the (small) transept organ. In the choir ambulatory, you'll find tombstone 99 of Netherlands' renowned composer Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1561-1621), who was associated with the Oude Kerk as the city organist during his lifetime. Another notable grave is that of Jacob Matroos Beeldsnijder in the Mary Chapel; as far as we know, he is the only black person buried in the Oude Kerk. He was the son of a senior official in Suriname and an enslaved woman. Jacob and his mother were owned by his father but were freed by him in 1781. His life story connects the history of the Oude Kerk with the African diaspora in Europe. In addition to graves, you'll also see richly decorated tomb monuments in the church. For example, that of the Dutch navigator Jacob van Heemskerck, who perished in the naval battle with the Spanish fleet near Gibraltar. He is further renowned for, among other things, his overwintering with Willem Barentsz on Nova Zembla in 1597.

Meeting place

The Oude Kerk has long been more than just a church. Besides its religious significance, the church has always been a vital part of Amsterdam’s social environment. Fishermen would mend their nets and sails here. For centuries, the most important city papers were kept in the Iron Chapel and countless lovers signed their marriage certificates in the Oude Kerk. The church was a place for trade and concerts and still has this versatile social function. The Oude Kerk is a lively meeting place in the heart of Amsterdam.

Contemporary art

The Oude Kerk invites artists and musicians to create new works in relation to the building’s history. We award two large art commissions annually to leading artists. An installation can adapt to the space or contrast with the historic environment. The commissioned works of art form the starting point for our extensive public program, such as the music series Silence, Monuments and also performances, guided tours and artist talks.